[

Last summer, Rebecca Croft came to the end of her tether. She’d spent the past six months reluctantly in charge of a bewildered, exhausted and demotivated team, having been parachuted into the role temporarily after the previous manager had gone off sick and never returned. Aside from a temporary salary increase, she was given no additional training for the role, no resources and felt constantly harangued from above by her own boss. Despite having no job to go to, Croft, 42, quit – doing so felt like the only way to escape the toxic situation she felt trapped in. “It felt like quite a risk,” she admits 12 months later, having found a new job. “I had a mortgage and bills to pay. But I knew that not getting out was going to be worse.”

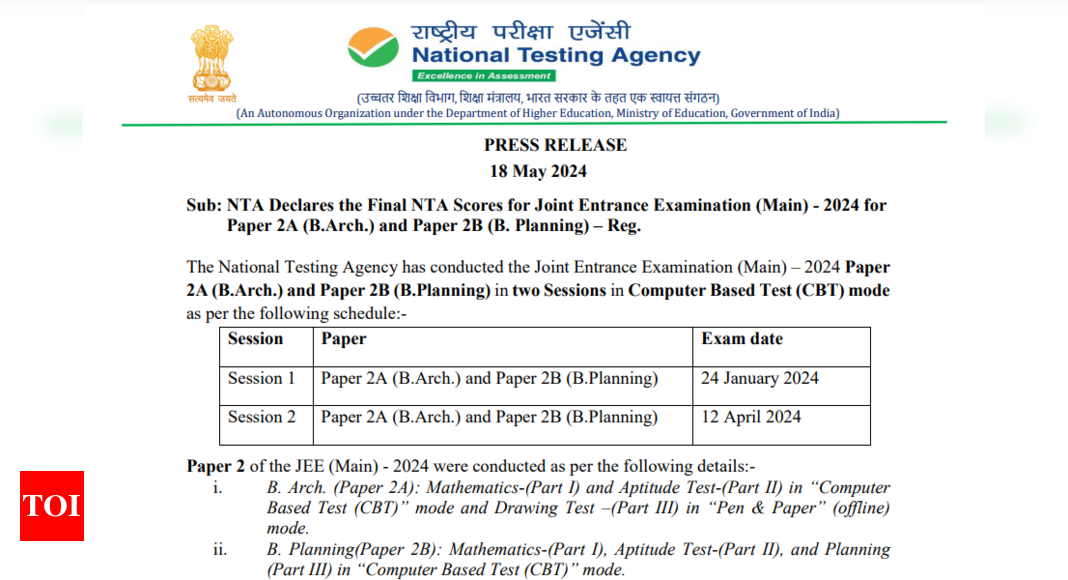

Croft’s experience is not unique. One in three UK workers have quit because of bad management, according to recent research by the Chartered Management Institute (CMI). It found that one in four working adults in Britain now holds a management position, and yet 82 per cent of those are “accidental managers”, having had no formal leadership training.

It’s having a disastrous effect on productivity: new data from the Office for National Statistics shows the number of people suffering from mental health problems caused by their jobs has soared by 275,000 since the pandemic. Experts say toxic workplace culture is often driven by reluctant – and insufficiently prepared – bosses. “The skill set of the average manager is so poor that the blind are leading the blind,” says communications expert and management coach Sue Ingram. “The vast majority want to be good, but don’t know how to do it – and don’t receive role modelling in how.”

So if you’ve got a bad manager, how can you spot the signs – and could you be part of the problem? “Sometimes younger millennials land in an office and think they’re going to have the perfect manager, but no person is complete,” points out former HR director Sally Harding. “Your boss could be a complete idiot and ridiculous at managing some things – but the first thing to do is make sure you’re not the solution, not just assume you can’t work with that person.” Here’s our guide to the seven types of bad boss, and how to deal with them.

The Control Freak

This micromanager is incapable of delegating or switching off, convinced that if the job is going to be done well, they’re the only one who can do it. The problem for their team is that it leaves employees feeling frustrated and belittled, not allowed any autonomy and with no opportunities to advance. This type of management is driven by fear, says Ingram. “They don’t feel safe unless they know what’s going on. If you’re one of them, it’s exhausting.”

A great, confident manager will be happy to let their team shine – “like the conductor of an orchestra”, says Ingram. “They might not know how to play the bassoon, or the flute, but they know how to get them to play together.” If they’re a control freak, they won’t be bringing out the best in them – and may waste time and resources “mansplaining” everything rather than listening to new approaches and ideas.

“I would take charge of my project and anticipate his needs,” advises Ingram. “Go in for a meeting, and say right, here’s an update on this project; I know what your next question’s going to be; here’s the answer.” “Sometimes you just have to grin and bear it,” says executive coach Audrey Wiggin. After all, she adds, what’s it costing you? If it’s just major irritation, you might have to just get on with it.

If you’ve got a control-freak boss, Ingram recommends something that might sound counterintuitive: praising them. “Show yourself to be 100 per cent behind them winning and looking good. They will then feel more relaxed about you because you’re anticipating what they need. It’s also worth being very explicit with this sort of boss: ask them exactly what they want, and how often they want you to report to them. Once everybody knows what is wanted, and the boss feels supported, it removes a lot of the tension, which allows the boss to loosen up too.”

The Bully

A third of workers will experience bullying at some point, according to the TUC – while the Health and Safety Executive says the problem costs UK businesses £18bn a year. Research in the Harvard Business Review identified 15 different types: a bullying boss may publicly undermine employees, by shouting or silencing them – or use more covert techniques, withholding information, gaslighting, and spreading rumours. Some bullies defend their management style as “having high standards” – but it is harmful and bad for performance. “A common assumption is that bullies are often star performers,” write the authors of the research. “However, the actual star performers are more likely to be targets than bullies. Research indicates that bullies often envy and covertly victimize organization-focused high performers — those who are particularly capable, caring, and conscientious.”

“The first thing is to say ‘Please, I need to ask you not to speak to me in that tone of voice, and then walk away,’” advises Ingram. “You don’t have to stand and receive the bullying.” When it comes to changing the situation, however, “this is the hardest one”, admits Wiggin. “It’s either about finding allies, or sometimes, if you have a proper grievance to bear, you have to call it out.” Harding agrees, recommending consulting those you trust before, for example, going to HR. If it’s really bad, your only option might be to try and get transferred to another team, or leave – taking the opportunity to be truthful (although not bitter or vindictive) in your exit interview. As Ingram points out, “your mental health is far more important than a job”.

The Offloader

Delegation is one thing; doing absolutely zilch is another. This manager is a master of the latter, rarely doing any of his or her own work, never getting stuck in, but just telling everyone else what to do – depleting all sense of goodwill or team morale along the way. Most frustrating of all is the boss who won’t pull their sleeves up, but will take all the credit. Research by the University of Exeter found “workshy bosses promote a contemptuous attitude amongst their staff leading to anger, frustration and abuse in the work place”.

“As a safety rule, you should always have a relationship with your boss’s boss,” advises Ingram, who advises building this relationship in, for example, the lift. Once that person sees you as a positive, high energy, problem-solving individual, you can go to him or her about a tricky manager and share your experience – making it clear that you’re not expecting them to solve it, you just want to tell them about it. Ingram successfully deployed this tactic herself with a lazy boss, and “I then got the manager’s job – because my boss’s boss knew enough about me that he could make his own mind up”. If you don’t want the top job, Wiggin advises giving your lazy manager a deadline: six months, say, and tell them what you need. Once they realise that you leaving would be a disaster (because you’re doing all the work), they’ll either pull their finger out or give you the reason you need to leave.

The Backstabber

This manager is out for themselves at all times, and will throw you under the bus if it saves their own skin. As with a bullying boss, such behaviour from a manager is often the result of their own insecurity. They may also be exhausted: research shows burnout among managers is at an all time high. “Be super careful here and manage your reputation,” advises Wiggin. “You know that if they’re going to talk about other people behind their back they’ll do the same with you. Don’t give them any reason to do so.” Ingram again underlines the importance of having a relationship with your boss’s boss. “Sometimes it can be mighty slow,” she says, “but their ship will eventually sink.”

The Robot

These people just have no idea how people tick. Bless them. That doesn’t necessarily make them bad at their job, say both Ingram and Wiggin – they’re often highly intelligent and very capable – just bad at the people who work for them. In other words, they’re the worst kind of “accidental manager” – highly successful as a practitioner, but no good at leading a team. It’s a growing problem, because advances in technology mean “soft skills” such as building trust and clear communication are more in demand among managers and executives than ever.

“Robots respond well to data,” says Wiggin. “Often, you have to just show them the data: tell them (subtly) that this is how people see them and this is the impact. More often than not they’re not doing it deliberately – once they recognise it and understand that a bit of emotional intelligence matters to other people, they’re normally willing learners.” She advises younger employees to suggest things – like team drinks – and offer to organise them. “Tell them you know it may not be their bag and ask them to come for an hour because you think the others would enjoy it and it would be good for team spirit.” And, adds Ingram, “do not ask them to do what they cannot do. They’re a human being struggling to do their job too – your boss isn’t supposed to look after you like a parent, they’re your work colleague. Find a mentor to fill that gap for you.”